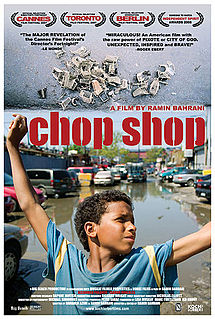

Ramin Bahrani tells us the story of an America that is excluded and marginalised, an America that lives on the fringes of well-being barely surviving with its handful of resources, an America that does not ridicule the American dream but rather mournfully observes the affluence that pushed it away. Chop shop is the story of that Americatn underbelly, seedy, sordid and gritty.

Ramin Bahrani tells us the story of an America that is excluded and marginalised, an America that lives on the fringes of well-being barely surviving with its handful of resources, an America that does not ridicule the American dream but rather mournfully observes the affluence that pushed it away. Chop shop is the story of that Americatn underbelly, seedy, sordid and gritty.

The twelve year old Alejandro works at the repair shop of New York. Occasionally he has to work as a street hawker or in a ‘chop shop’ (Chop shop is a workshop where a vehicle, often stolen, is dismantled and sold in parts). His sister Izzy works on as a food supplier from a van while at night secretly sells her body in order to earn enough money to rid themselves off the poverty by trying to realize their mutual dream: to own a food supply van.

Eventually, through their hardship they manage to gather enough bucks tho buy a dilapidated van from Ale’s friend Carlos’ uncle only to be informed later that the van is not fit for the purpose and would cost too much to fix. Enraged, he attacks Carlos in public, only to understand the futility of the whole scheme: their endeavours and their dreams, their struggles and their vain attempt of escaping, all are meant to feed another chop shop where every part of their soul is to be broken, shattered, dismantled and sold cheaply as a part of an exorbitant dream.

The way Bahrani approaches the nude and rude realism frame by frame is immensely laudable. One cannot help but observe the effects of the neorealist movement of Iranian masters in the work of this promising film-maker who is, certainly, going to provide many more gems in days to come.