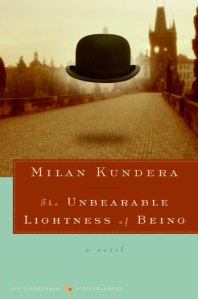

The Unbearable lightness of being is definitely an out of the track work by Kundera with whom I fell in love after going through his first novel, the Joke. The tale or rather the multiple stories hidden inside the Joke makes it a complete novel while the Unbearable Lightness of Being, though more critically acclaimed, lacks. The tales inside this novel maintains coherency by keeping the main character Tomas in its centre, but the stories have failed to become as intriguing as those of the Joke. If Joke is a novel about disillusionment and underlying bitter sarcasm inside the most serious situation, then Unbearable lightness of being is a novel of philosophical outlooks at a time and in a world when all the philosophical saying seems to be losing their meaning very fast. Or rather it is not a novel at all, but a bunch of answers that the writer wanted to give, may be to himself, may be to the rest of the world, and so he has invented the questions in the form of a few invented situations and a few half-told stories that were explained rather than being told. So going through this piece of beautiful literature entails an im mersion into the realm of solitude that is shared by the author with his constant effort to fill up the void with the stream of philosophising.

mersion into the realm of solitude that is shared by the author with his constant effort to fill up the void with the stream of philosophising.

The story of Unbearable lightness of being is apparently a period drama that is set across the 1968 invasion of then Czechoslovakia by the USSR. The so-called Prague spring followed by the USSR invasion is depicted in the novel with a dry humour without any attempt on the novelist‘s part to become a historical commentator. To the relief of the reader, the chronological account of day-to-day activity was not given (that would have been really harrowing, especially for someone like me who already has some substantial idea of the happenings of that period). Anyhow, the novel mostly revolves around the relation between the central characters like Tomas, the surgeon (it’s curious how Kundera loves making his protagonists doctor. Thankfully he refrained from that while writing Life is elsewhere), his wife Tereza, his free-spirited lover Sabina and Sabina’s lover Frank, another married man having illicit affairs with her. Sounds hackneyed! Surprisingly, it is not. The apparently clichéd plot of married man fooling around behind the back of their demanding wives metamorphosed into one of the greatest novels of twentieth century with the magic wand of Kundera. It is breathtaking how effortlessly Kundera goes deeper into every relations, removing one layer after another and finally ends the concludes the novel with multiple tragic incidences as the novel was supposed to be. There was no pretension of making this novel into an experiment with form or striving to produce a work of Homeric volume. All along, Kundera works on his strength, namely, to depict and analyse a more or less commonplace situation (with a tint of political and psychological extra-ordinariness) to a vividity that only a clear thinker as Kundera is able to. His incisive mind, almost as limpid as a dispassionate rationalist philosopher, gave rise to the work that, sadly, would be remembered as a futile hollywood endeavour, but truly is a masterpiece. True, this is not my favourite novel of Kundera, (mine is Life is elsewhere), but with the sheer amount of region his novel covered, the multifarious qualities he endowed his characters with and yet making them represent various aspects of human mind and philosophical currents, deserves to have a standing ovation. For example, the character of Franz, an idealist man submerged into academic world, having a self-righteous feel about himself and yet too removed from the world of happening to do something about it and to gratify his need to see himself as one greater-than-thou. How with a single character, Kundera captures multitudes of academics of the first world rueing through the same fashion!

Similarly, for a ‘free-spirited’ woman, Sabina is far away from being a prototype. Sometimes she becomes the representative of the escapist view of life, sometimes she is the captive soul willing to belong, sometimes she is the confined dehumanized representative of the oppressed people of an oppressed nation whom her surroundings showers in pity and hence denies herself to be an individual: the only thing she longs to be.

Tomas and Teresa and their relationship encircles so many different themes, from Christian morality and mythology to end of the age of ideas, that would take another book to comprehensively cover them. Suffice it to say that they truly became the voice of dissent and deliberation that Kundera needed to deliver this complex novel full of ideas. Reading back in a new century, when the world faces another disillusionment, when the promises and glitters of globalization was not delivered, we stand, once again on the same ground of awakening, looking for a voice as clear as Kundera’s to end our dreams.

Daily Archives: April 2, 2013

Aegis

The shell is strong

Strong enough to hold up

Against all the lure and love

All the affection and pity

All the scorn and disdain

All the glories and promises

All the persecutions and vindications

That you can throw at me.

For ages now I am living inside Aegis

Which has become a part of me;

Or I a part of it;

I don’t know nor want to

If there is any escape out of this.

You say I’m caged

You say I’m locked

You say I’m withdrawn and afraid

I say I’m protected and covered

And warm that no spring can enter me.